There was a large amount of secular musical activity during twelfth, thirteenth and fourteenth century but since much of it relied on the oral tradition little was written down. The goliards, jongleurs, gaukler and the troubadours and trouvères all contributed to this. But even of the songs of the noble and literate troubadours, while we have 2600 texts only 246 melodies survive; here’s an example:

Guiraut de Bornelh (c. 1138 — 1215):

Reis glorios

Glorious king, who heaven and earth did make,

Almighty God, Lord for sweet pity’s sake,

Protect my friend, I pray, who is not deeming

That sunlight soon will o’er the earth be streaming,

And soon will come the morning.

We have little idea of how these poet/musicians accompanied themselves. They’re frequently pictured with instruments but we can only guess how the music itself sounded. But was seems certain is that, as with any songs, the concentration was on the melody.

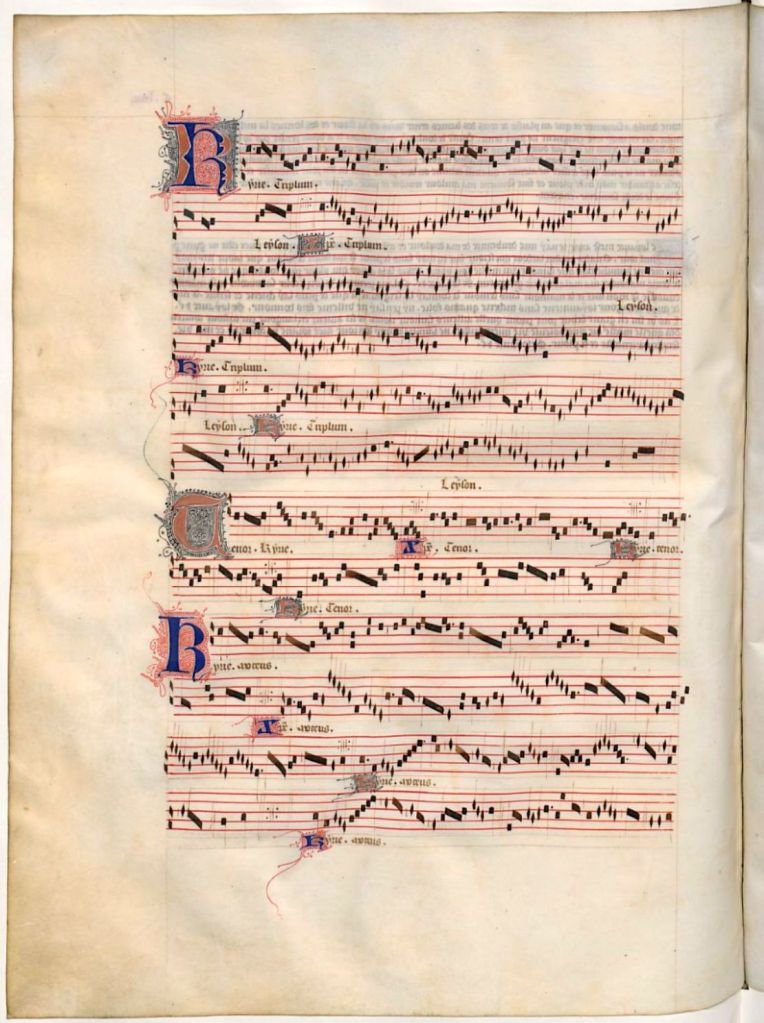

It’s this focus on the horizontal melodic line rather than the vertical ‘chords’ of accompaniment that is a feature of much of the music of this period. Here’s a famous example: the first through-composed setting of the ordinary of the Mass by one of the fourteenth century’s greatest composers and poets, Guillaume de Machaut.

Guillaume de Machaut (c. 1300 — 1377):

Messe de Nostre Dame

One of the consequences of this horizontal thinking was the caccia. A canonic form (think of Frère Jacques or London’s Burning) frequently for two voices chasing one another with the same tune at the same pitch (in other words a two part round) with a third independent, supporting voice underneath. Here Gerald of Florence makes a nice pun on the word caccia since in Italian it not only means a musical chase but also the pursuit of some poor, unfortunate animal i.e. hunting. It’s a brilliant piece and includes all the sounds of the hunt including, at the end, the ‘mort’ sounded on the corno da caccia (the hunting horn).

Gherardello da Firenze

(c. 1320–1325 – 1362 or 1363):

Caccia: Tosto che l’alba

Tosto che l’alba del bel giorno appare,

disveglia gli cacciatori:

“Su, ch’egli è tempo! Alletta gli cani.”

“Tè, Viola! tè, Primiera tè!”

“Su ‘alto al monte co’ buon’ cani a mano

e gli brachetti al piano

e nella piaggia a ordine ciascuno!”

“Io veggio sentiro uno de’ nostri miglior bracchi!”

“Sta’ avvisato!”

“Bussate d’ogni lato ciascun le macchie,

chè Quaglina suona!”

“Ayò, ayò! A te la cerbia vene!

carbon l’a pres’ed in bocca la tene.”

Del monte que’ che v’era su gridava:

“A l’altra, a l’altra!” e suo corno sona.

As soon as the dawn of a fine day appear

It awakens the hunters.

“Get up! It is time! Rouse the dogs!”

“Up, Viola! Up, Primera, awaken!”

“Up the mountain now, with the good dogs on their leashes,

and the hounds down on the plain,

and on the mountain’s side every one in place.”

“There, I see one of our best hounds sniffing!”

Watch out!”

“Beat the bushes on every side

the horn is sounding!”

“Hey, hey! The deer is coming your way!”

Carbon has caught it in his mouth and is holding it!”

The man who was up on the mountain called out:

“Now to the other deer!” And he blew his horn.

Any copyrighted material on these pages is included as “fair use”, for the purpose of study, and critical analysis only, and will be removed at the request of the copyright owner(s).